The Chickens of Ancient Egypt - Part 2

In Part 1, I reported my research into the beginnings of chickens in Egypt. Everything that I found pointed toward chickens arriving with the Persians after their invasion in 525 BC. The Persians had chickens and they obviously brought them along. After the Persian conquest, chicken references in the Egyptian written record became quite common.

But there’s a problem. There are ancient recorded instances of chickens clucking and pecking around Egypt before the Persians arrived. Way before! Thousands of years! These ancient chicken mentions are rare, but they are real!

So I rolled up my sleeves and tackled those aberrant early sightings. Here’s what I figured out.

Those Confusing Chick Hieroglyphs – 3100 BC

Chick hieroglyph - Ramses IV tomb - Valley of Kings (photo - Randy Graham)

As I visited the Cairo museums and toured the old tombs in the Valley of the Kings, the chicks surprised me. There were pictures of chicks everywhere among the hieroglyphics. I knew that hieroglyphics went back to the very beginning of Egyptian civilization. And I knew that chicks didn’t. This confused me, so I asked our tour guide about it.

She told me that the chick was very common because it represented a common sound. It is phonetically equivalent to either a “w” or “o” sound. I was still confused. What did the Egyptians use to represent those sounds before there were chickens, I asked. She looked at me blankly. Then she explained that she supposed that in the early Bronze Age, over 34 centuries ago, before hieroglyphs’ sounds became established, the chick hieroglyph represented nothing more than a chick. I gestured my frustration. There were no chicks 34 centuries ago, I told her. She repeated her blank look. She didn’t understand the point of my question.

So, then I asked Google. Google cleared up my confusion. Once source: “The original of the [chick] hieroglyph however is almost certainly to be found in the quail.” Oh! All those hieroglyph chicks are not chicken chicks. They are quail chicks. Quail were native to Egypt. Phew. Confusion resolved.

Hieroglyphics - Nefertari tomb - Valley of Queens (photo - Randy Graham)

Howard Carter’s Ostracon – 1425 BC

Many have said that the character of Rick O'Connell, the swashbuckling archeologist in the 1999 movie, The Mummy, is based on Egyptologist Howard Carter. But Carter was nothing at all like that. Carter was driven and dedicated, with a deep passion for the ancient civilization of Egypt. He was known for his meticulous attention to detail and his careful approach to excavation. He was also a combative loner; a perfectionist who demanded excellence from himself and his team.

Howard Carter (public domain)

After a sickly childhood with little formal education, he found his way to Egypt in 1891, at the age of 17. There, he used his artistic ability to gain a position copying the decorations in tombs undergoing excavation. Because of his hard work, systematic methods, and his eye for detail, he worked his way up from teenage copy artist to the position of Inspector of Monuments for Upper Egypt. And then, he became iconic for his 1922 discovery and excavation of the nearly intact tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings.

Carter’s life’s work was in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings—the desert location of the tombs of many of Egypt’s pharaohs on the west bank of the Nile. He built his house there; a blocky stucco structure with thick walls to keep out the desert heat and a domed roof to aid ventilation. For many years after Carter’s death, his house moldered, empty and abandoned. But the government of Egypt recently reclaimed and restored it and has made it a museum. I paid a visit.

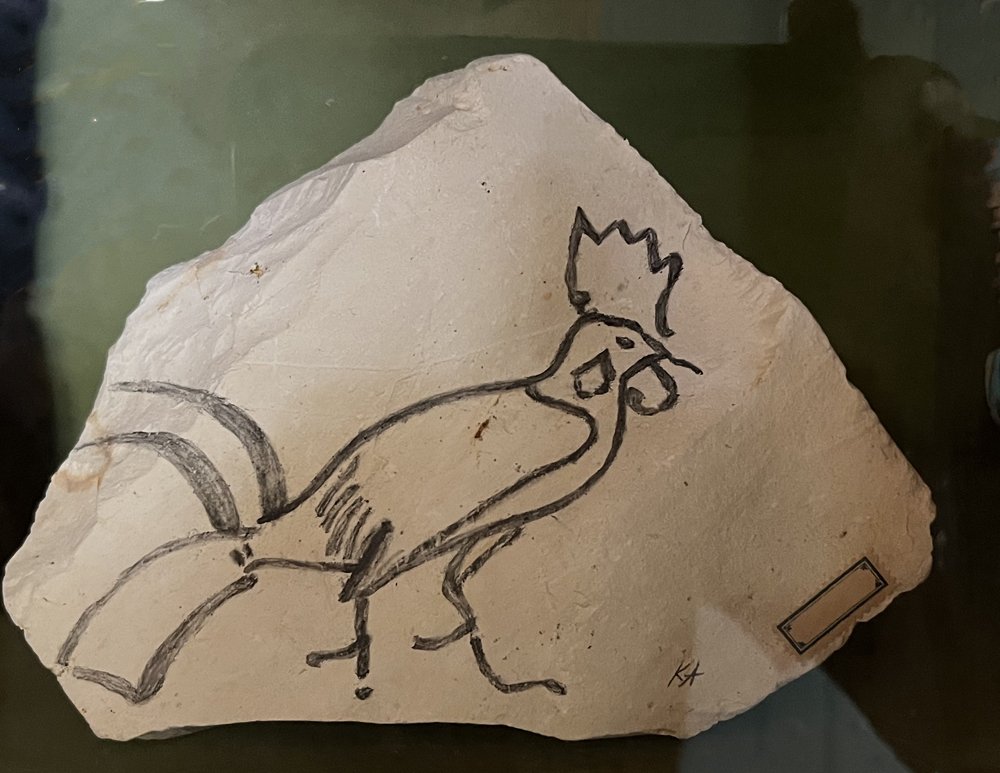

In a display case in a corner of one small room, I spotted Ostracon 341. I was delighted. It was not labeled and it lacked any sort written description explaining its significance. I knew about it, though, and I was careful to get some good pictures with my phone. Also, I knew that it had to be a replica, since the original resides in the British Museum.

Ostraca (the plural for ostracon) are ancient Egyptian post-its. Scribes etched important declarations in stone monuments. And they wrote vital records on papyrus. But inscribing in stone was time consuming and papyrus was expensive. So, to write notes, lists, messages and doodles, they picked up the shards of broken pottery that were laying around practically everywhere. Nice flat writing surfaces that were free-of-charge. Ostraca!

The discovery of Ostracon 341 is just one example of Carter's keen eye for detail and his ability to recognize the significance of even the smallest finds. The big deal about this ostracon? It depicted a rooster! And the reason that’s a big deal? At the time, it was the only known example of an ancient Egyptian representation of a rooster. Carter recognized the importance of the find, studied it extensively, and published a paper about it in 1923 in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology.

Ostracon 341. So cool! (Photo by Randy Graham)

In that paper, Carter describes how “it was discovered during the winter season 1920-21…in the lower undisturbed stratum between the tomb of Rameses IX and the 18th Dynasty tomb-chamber wherein the cache of Ikhaton was made.” Based on its stratum location, Carter determined that it “may be dated as…not later than the period of the tomb of Rameses IX…or in other words circa 1425-1123 BC.”

“We have before us,” Carter declared, “not only the earliest drawing of the domestic cock, but absolute authentic evidence of the domestic fowl…being known to the ancient Thebans [ancient Egyptians living near present-day Luxor]. Before this discovery, Carter wrote, the “earliest examples in Egypt of the cock I have heretofore known were the red pottery vessels of the ornamental type” that were probably of the Ptolemaic period (well after the Persian-conquest, thus over a thousand years more recent than this ostracon).

Why was this scratch-paper sketch of a rooster here? It was entirely in the wrong place at the entirely wrong time. The artist had obviously seen a rooster. Carter speculated that it was perhaps a red jungle fowl—the wild progenitor of domestic chickens. Chickens were, in fact, already domesticated then. But they were in far-away Asia. As were, for that matter, red jungle fowl.

There were trade routes between Mesopotamia and India (where there were chickens), as well as between Mesopotamia and Egypt. Maybe an occasional chicken lived in Egyptian royal zoos or gardens. And perhaps somebody, after viewing one, was inspired to pick up a pottery shard, and draw a picture to show his friends. He could tell everybody, “Hey, I just saw this strange bird!” And then pass around his drawing.

Carter knew of one other possible recorded reference to chickens from the same period and mentioned it in his paper. He states that “In Egypt,…the domestic fowl is nowhere depicted upon [ancient] monuments… with the exception of perhaps one possible instance…There appears to be a reference to the Red Jungle-fowl in the famous Annals of Thutmose III.”

Who was Thutmose III? Why was he talking about chickens? I tracked him down in the great Karnak Temple in Luxor.

The Plundered Birds of Thutmose III – 1446 BC

Walking among the ruins at the Karnak temple in Luxor is awe-inspiring. First, the ruins at this ancient site are so unruined. Walls still stand; columns and obelisks remain erect. And after some restoration work to remove centuries of grime, columns and walls still display their original pigments.

Second, the magnitude of the temple is amazing. It covers about 200 acres. The sacred enclosure of Amun encompasses sixty-one acres. It could contain ten average medieval European cathedrals. The Great Hypostyle Hall contains 134 massive columns, each over 20 meters high, and covered with intricate carvings and inscriptions. The Avenue of Sphinxes, a ceremonial processional route that connects the Karnak temple to the Luxor temple, is 1.7 miles (2.7 km) long and is flanked on both sides with over 1300 sphinxes.

A portion of the Avenue of the Sphinxes (photo - Randy Graham)

And third, it is such an ancient place that I could sense the aura of its age as I walked through its passages. It’s beginnings date to nearly four thousand years ago. Successive pharaohs expanded and developed it over a period of nearly 2000 years. During that great span of years, millions of people filled its courtyards and walked its maze of corridors . People alone or with their friends or families. Worshipping, laughing, weeping, dreaming, hoping, dreading, doing business, performing rituals, praising their gods, making political deals, living, dying. Or awestruck, like I was as I wandered the labyrinth of glyph-filled walls.

I was delighted that I managed to stumble across Pharaoh Thutmose III’s tribute wall as I negotiated the vast expanse of this temple complex. I lingered by the wall for several protracted minutes until the other tourists had wandered away. I needed to spend some time alone with Thutmose’s account. I took some pictures. Then, after some hesitation and self-consciousness, I reached out and laid my hand on the wall. An anonymous worker stood here and inscribed these stones with Thutmose’s story thousands of years before I touched them. Unfortunately, I don’t read hieroglyphics. But I already knew what was written here.

Thutmose III statue - Luxor Museum (public domain)

Thutmose began his rule of Egypt in 1479 BC when he was a two-year-old. His aunt/stepmother, Hatshepsut, served as his coregent for the first 22 years. He ruled until his death at the age of 56. Thutmose ruled Egypt during the “New Kingdom” period when Egypt was at the very pinnacle of its power. And Thutmose is considered to be one of the most powerful rulers of the period. He conducted seventeen military campaigns, took control of much of the Middle East to the east and Nubia to the south, and expanded Egypt’s territory to the largest it ever held.

We know about Thutmose’s achievements because his faithful royal scribe directed that they be etched into the Karnak temple wall; the wall that I was fortunate to view and touch three and a half millennia later. The Annals of Thutmose cover a space about 82 feet (25 meters) long by 39 feet (12 meters) high. The account begins with the first campaign – the battle to take Megiddo (in present-day Israel). The inscribed hieroglyphs describe the campaign in great detail—the journey, Thutmose’s meetings with his generals, the battle, the ultimate victory, and the taking of tribute.

After Megiddo, there followed sixteen more campaigns. It seems that the scribe lost his enthusiasm for the project as one campaign followed the next. Most of the later campaigns get only brief descriptions, and by the final campaigns there is no detail. Only long lists of war plunder.

A section of the Thutmose III tribute wall - Karnak Temple, Luxor (photo: Randy Graham)

Buried in the recitation of war tributes, is the passage that piqued the interest Howard Carter, and, well, me too. German Egyptologist Kurt Heinrich Sethe was the first to write about it. In his 1916 paper, “Die Alteste Erwahnung des Haushuhns in einem Agyptiscen Texte,” Dr. Sethe transcribed a portion the Karnak annals. It describes how in his 8th campaign, Thutmose took his army far into Babylonia. There, he conquered a land near Syria whose name is lost. Among the war tribute that Thutmose took home from that unnamed land were several varieties of birds. Four of the birds were of a type that do [something] every day. What did the birds do? Unfortunately, there is a lacuna, a damaged bit, right at the critical word. Earlier transcribers supplied the verb “sing.” Very logical. Birds do sing. Every day. But don’t all birds sing every day?

Then Dr. Sethe paid closer attention to the still-legible edges of the missing hieroglyph. The hieroglyph for “bear” would perfectly fit with the visible lines. “The birds that bear every day.” We know what bird lays eggs every day, right? The English translation of Sethe’s 1916 paper is “The Oldest Mention of Domestic Chickens in Egyptian Text.” Howard Carter, in his 1923 paper, concluded that “Our ostracon certainly bears out Sethe’s…hypothesis.”

It is only a hypothesis that the birds described in Thutmose’s annals are chickens. But it is a hypothesis that is both compelling and reasonable. Thutmose was all about war treasures—to the degree that he had them all recorded on the walls of the temple. And what could be a better treasure than these strange and beautiful birds that laid eggs every day! I doubt that he ever considered the possibility of eating these rare creatures. He probably had a menagerie of exotic animals from the lands he had conquered. I like to think that those four sweet birds stayed there in pampered luxury for the rest of their lives.

And perhaps there were babies. Maybe the offspring of their offspring served as the model for the chicken on Howard Carter’s ostracon. And why not speculate that many, many generations later their descendants mated with the tsunami of Persian birds that swept into Egypt, thus keeping their bloodlines alive. Maybe when I stared into the tiny cage in the Esna market, the hens staring back possessed in their blood a tiny fraction of the heritage of that ancient pharaoh’s hens.

I said before that reaching into that cage in Esna it was my only Egyptian chicken experience. But that’s not entirely true. My exploration of Egypt was an amazing journey. And that journey sparked my odyssey of research and discovery that resulted in the story that you’re reading right now. That second odyssey is also part of my Egyptian chicken experience. And that, also, was an amazing journey.

Esna hen - (photo - Randy Graham)