Chickens from Outer Space? The Strange Case of South American Chickens

I’ve always been interested in ancient sites and am fortunate to have been able to visit a few of them over the course of my life. Unsurprisingly, when I visit these sites, I often meet others who share my interest in timeworn architecture and ancient civilizations. I also bump into another whole subset of people at these old places—those searching for sites imbued with “secret, ancient power”. Visit Stonehenge, Angkor Wat, or Machu Picchu and you’ll run into them, alone and in groups, in shorts and hiking boots or robes and beads, seeking healing, omens, visions, or doorways into other dimensions.

And sorry, but I’m very skeptical. I think these nice people are earnestly looking for something that is just not there. So, when the wide-eyed “seeker” at Machu Picchu announces “When I stretch out my hand over the Intihuatana I can feel energy!” I respond, “Um, yeah, The Intihuatana is a massive rock that’s been sitting in the sun all day. Why wouldn’t you feel energy? It’s called ‘radiated heat’.” Or they say “When I put my head in the niches of the Sun Temple and hum, I hear the other-worldly reverberations!” And I reply, “Have you tried humming with your head in a garbage can? Same effect.”

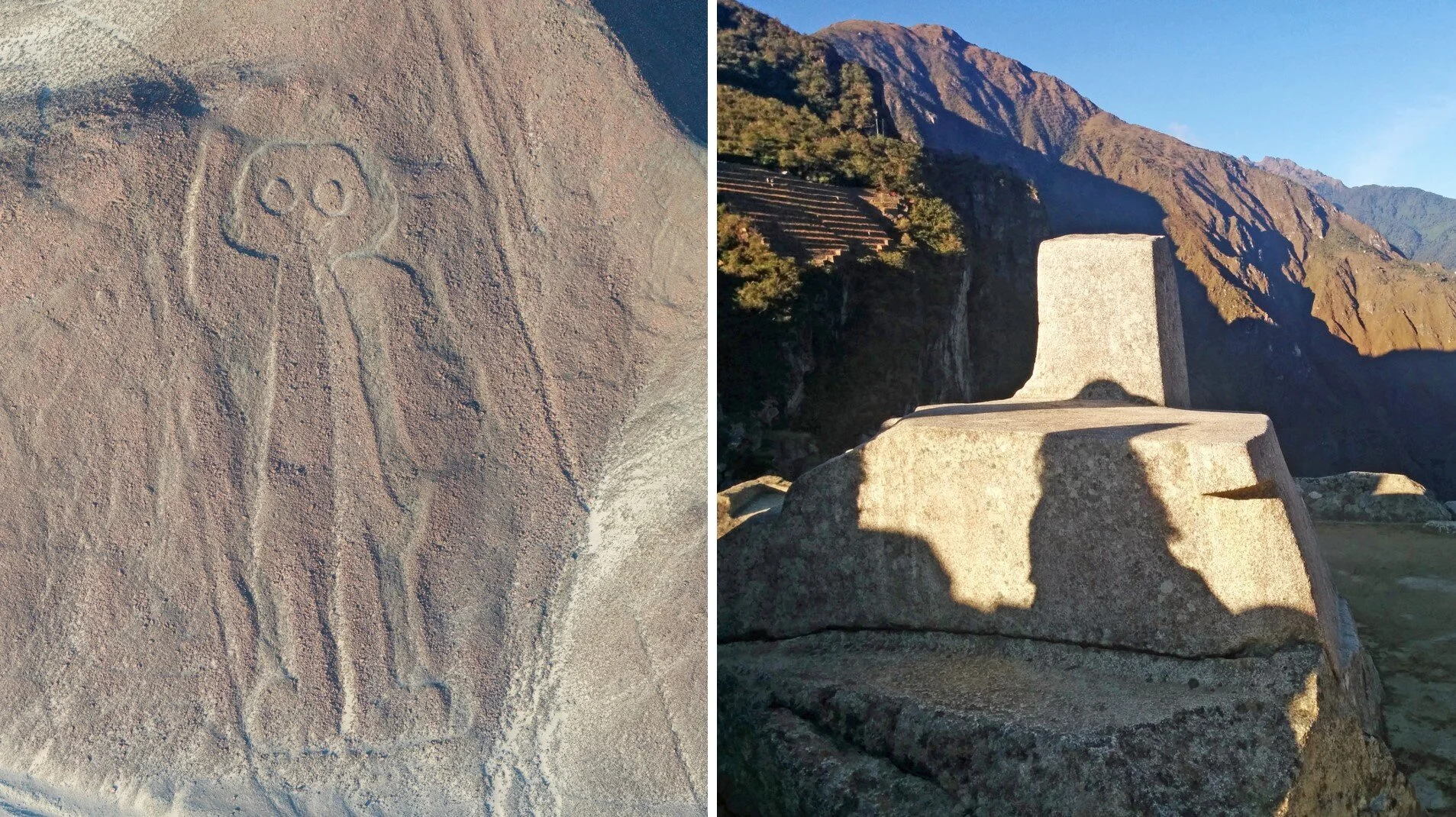

OK, so maybe my feet are planted just a little too firmly on the ground, but I will admit that even I was very much in awe of the grandeur, and yes, the mystery of Machu Picchu. There’s a lot of really mysterious stuff going on in South America. In Ollantaytambo, an old site not far from Machu Picchu, I could not imagine how ancient South Americans who didn’t have the wheel were able to move a bunch of monoliths weighing 50 tons each to the top of a mountain from a quarry site over two miles away. And I continue to wonder how and why ancient South Americans drew lines in the Nazca desert 250 miles south of Machu Picchu that from the air are obviously giant pictures of animals, birds, and fish, but from the ground are meaningless. Because ancient South Americans couldn’t fly. Right? And I wonder about South American chickens. “Wait…what?”, you ask, “Did you say chickens?” Yes. Chickens. This is a chicken blog, you know. And there’s something reeeaaalllly weird going on with South American chickens.

(lt) An aerial view of one of the giant drawings in the Nazca Desert. Is this a human, or is it a chicken? Or is it an alien? (Credit: Diego Delso, delso.photo, License CC-BY-SA) (rt) The Intihuatana at Machu Picchu - ancient sundial - and also a source of energy? Who knows?

Not only are South American chickens very strange birds, but they’ve been in South America way too long. When the Spanish first arrived in South America they noted the fact that there were already chickens there! People were keeping domestic chickens! Chickens, like cows, pigs, and sheep, are supposedly Old-World animals. So what were they doing in South America before the Old-World explorers/conquerors got there? How did they get there? Flying saucers, anybody?

Now that I’ve got your attention, let’s back up and look at the South American chicken conundrum point by point.

South American Chickens are Unique

About 9000 years ago, somebody in East Asia domesticated the chicken. Every chicken alive today is descended from the East Asian jungle fowl, and like every other domestic animal, they have changed from their wild ancestors and developed a wide variety of forms. Today there are hundreds of breeds of chickens, each with its own characteristics—different sizes, feathers in an assortment of patterns and colors, and even eggs in a range of sizes and colors.

A variety of chicken breeds (and Guinea fowl for some reason) - Public Domain - Library of Congress

Some of the most unique chickens in the world come from South America. Araucana chickens, whose bloodlines are all South American, are tailless chickens that have interestingly tufted ears and lay blue eggs. The Araucana breed was developed from chickens acquired from the Mapuche people of western South America (a group whom the Spanish originally referred to as the Araucanos). Taillessness, or rumplessness, has arisen several times and in several chicken populations around the world as a spontaneous mutation – all rumpless chickens alive today are descended from these mutations. The blue egg mutation has only occurred twice – once in China and once in South America – thus all blue-egg-laying chickens are descended from one of these two original populations. The ear tufts mutation only occurred in South America so all chickens with ear tufts have South American ancestry. The tufted ear trait is not an easy one to pass on since it is caused by a “homozygous lethal gene”. If a chick gets genes for ear tufts from both parents it will die in the egg prior to hatching due to a malformation of its throat and ear channel. So tufted chickens are carrying the tuft genes from only one parent and if they mate with another tufted chicken, only half their offspring will be tufted. One quarter will be non-tufted, and one quarter will die before hatching. The rumpless gene, by the way, is also a “homozygous lethal gene” resulting in a 25% pre-hatch mortality. Doesn’t it seem unlikely that chickens with this lethal combination of traits can even exist?

(l) Bonnie demonstrates rumplessness (m) Blue egg courtesy of Veronica (r) Sam demonstrates ear tufts

How Did Chickens Get to America Before Columbus?

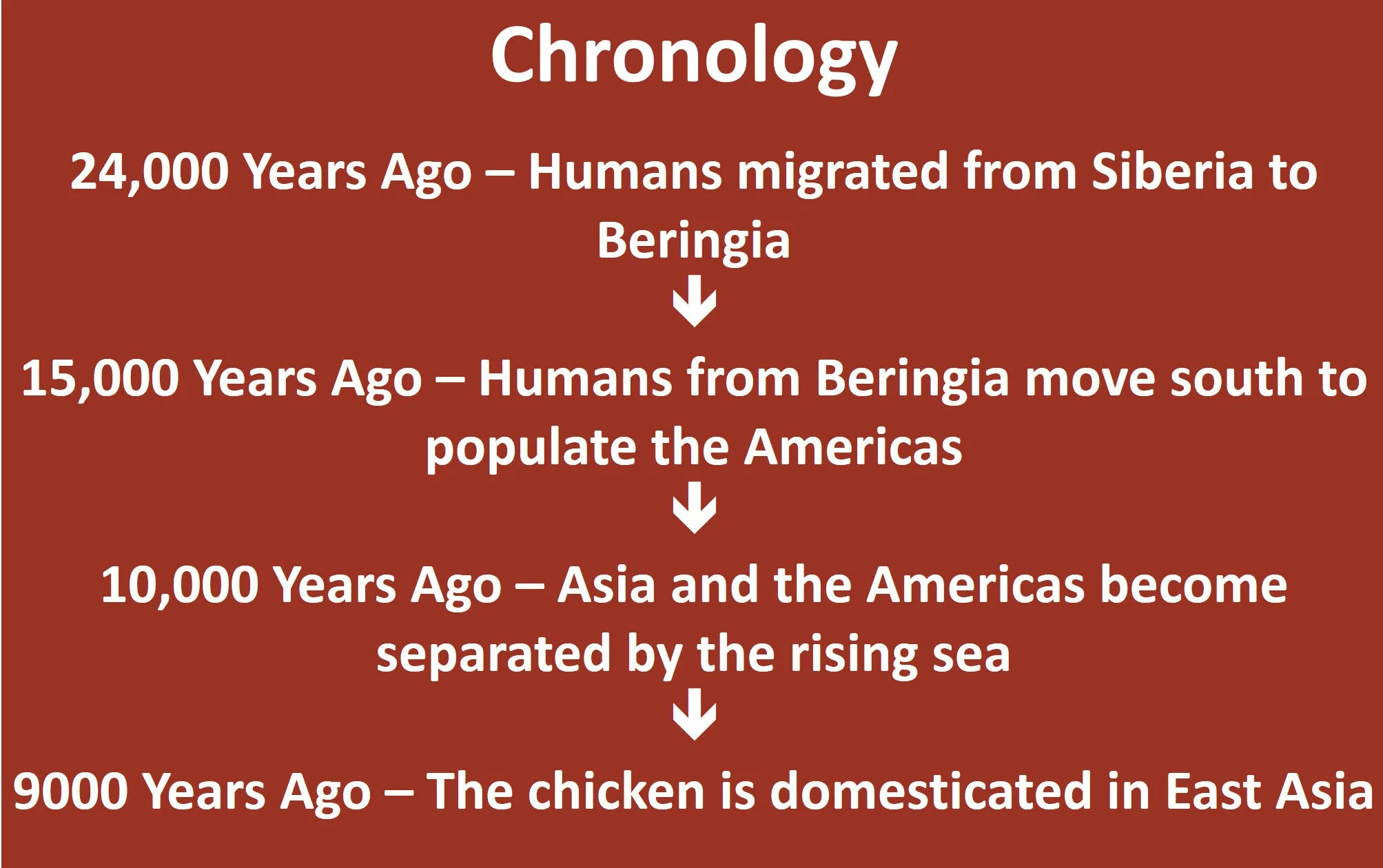

Then there’s the matter of these improbable birds existing in a place they shouldn’t be. There’s an enormous problem with the first Spanish explorers finding domestic chickens in South America: The first humans came to the Americas about 15,000 years ago. Scientists are continually gaining a clearer picture of the populating of the Americas through the study of geology, ancient climates, carbon-dating of archaeological relics, and the analysis of Native American DNA and languages. All of this scientific work points to human migrations from Siberia to Beringia around 24,000 years ago. Beringia was an area about the size of Texas that connected Siberia with Alaska. It was mostly surrounded by glaciers and was dry land because the ocean levels were much lower since so much water was locked up in glacier ice. The human migrants lived in Beringia for thousands of years and became genetically distinct from their Siberian cousins. As the last ice age began to end and gaps opened up in the glacial wall to the south, the Beringians traveled south and populated the Americas. The largest migration started 15,000 years ago and there were a few smaller ones after that. Thus, the Beringians were the ancestors of all of today’s Native Americans. By 10,000 years ago, the glaciers had melted so much that Beringia flooded and Siberia and Alaska became separated by water. From that point forward Beringia has existed only beneath the ocean waves and there has been no land connection between Siberia and the Americas.

“But what about the chickens?” you ask. “You said this was a chicken blog, so what about the chickens in South America?” Well, here’s the deal – if you scroll back up to the 6th paragraph, you’ll note that chickens were domesticated 9000 years ago. Beringia disappeared under the ocean 10,000 years ago—a thousand years before the domestication of the chicken, cutting off Asia from the Americas. The timelines don’t mesh. The hunter-gatherers heading south from Beringia 10,000 years ago, ancestors to today’s Navajo and Dakota, as well as the Aztecs, the Incas and all other Native Americans were not carrying chickens. Yet when the Pizarro arrived in Peru in 1532, he found chickens happily clucking, pecking, and scratching in the American soil!

“Well that’s pretty weird,” you probably say. “But we all know that in 1492 Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue and landed at the Bahamas and then made a few more trips after that. Isn’t it possible that he introduced chickens on one of his voyages and they found their way to the Inca settlements for the Spanish to make note of 40 years later in 1532?” “Logical point,” I say. But then there’s this. There are numerous early references to the use of chickens in Incan religious practices. Would the Incas have been able to get chickens through some sort of trading network with others who had already been in contact with the Spanish and then so thoroughly incorporate them into their culture that they were being used for religious ceremonies in span of a mere 40 years?

And there’s this. Father José de Acosta, a Jesuit priest spent time living among Quechua-speaking Indians in Peru in the late 1500’s. (Quechua is the language of the Incas – it is still spoken today in many areas of Peru.) In 1590 Father Acosta published a book entitled “Historia Natural y Moral de las Indias” and in that book he lists the Quechua words for a variety of animals. It is natural the Inca would have used the Spanish name for animals introduced by the Spanish since they had never seen those animals before and had no name for them. So, in Quechua, horse is kawella (Spanish for horse is caballo); cow is waca (Spanish for cow is vaca); and sheep is oweja (Spanish for sheep is oveja). See the similarity? Then we look at chicken related words – Quechua words for hen, rooster, and egg are achawal, alkaachawal, and runtu, respectively. Which are nothing at all like the Spanish words naming the same things, gallina, gallo, and huevo. Which suggests that hens, roosters, and eggs were already known to the Inca before the Spanish arrived.

And then there’s this. In 2007, Alice A. Storey, an anthropologist at the University of Auckland, New Zealand, published a paper about an archaeological dig at a place called “El Arenal” in south central Chile. They found pottery shards at the site that they dated, using thermoluminescence to 1304-1424. And they found chicken bones as well that they radio-carbon dated to the same time period – long before Columbus sailed the ocean blue!*

Needless to say, this got the attention of the entire scientific press, and it also generated tons of controversy. Another researcher tested the bones and found them not to be that old. Then others tested them as well, and by today it is fairly accepted across the scientific community that the bones really are that old.

Dr. Storey was able to extract DNA from those old bones and when she compared that DNA with the DNA of other chickens she found a match with the DNA of Polynesian chickens. Suddenly it all made sense! Polynesians are known have populated islands across the Pacific by navigating huge swaths of oceans in their canoes. It was very plausible that they would have found their way to South America’s west coast, and that they would have brought their chickens with them.

Then there was more controversy. In 2008 and again in 2014, other studies showed that there was absolutely no real similarity between the Polynesian chicken DNA pattern and that of the El Arenal DNA or DNA of modern South American chickens. And that’s where we are today. We have South American chickens that are genetically unique- different genetically from both European and Polynesian chickens and also genetically implausible because of two sets of lethal genes. And many indicators point to them being in South America for a long, long time – long before the Spanish arrived. So, where did they come from and how did they get there?

Flying saucers, anybody?

From "Plan 9 from Outer Space - Public Domain - Wikimedia Commons

*In my original post, I said that the El Arenal pottery shards were radiocarbon dated. Radiocarbon dating cannot be performed on material that was never alive. In fact the shards were dated using thermoluminescence dating.

This post was originally published on Randy’s Chicken Blog on October 31, 2017.