Can I Catch Bird Flu From My Chickens? Will it Cause the Next Pandemic? (Flu - The Coop, part 3)

Also in this series:

Part 1 - Two Viruses

Part 2 - Bird Flu 101

This year, for the first time since 2016, highly pathogenic bird flu has been marching across the US and destroying poultry flocks along the way. And while the march has significantly slowed lately, it’s still out there. The most recent US case, as I write this article, was detected in a backyard flock in Florida in late July. In every case, when this deadly disease finds its way into a coop, the outcome is devastating. Mortality approaches 100%. If you lose a bird to highly pathogenic avian influenza, you are on the cusp of losing your entire flock.

But what about people? Since bird flu first appeared in the news this spring, people have been asking questions about bird flu as it relates to them. “Can people catch this disease from chickens?” “If people can catch it from chickens, what are the consequences for the infected person?” “And if people can catch it from chickens, how great are the chances that they actually will?” “And if people can catch it from chickens, will this bird virus start a flu pandemic in people?” “Oh! And if people can catch it from chickens, what about the fried chicken dinner I had yesterday? Am I already doomed?”

Well, good news if you’re sweating the fried chicken. You’re going to be fine. The chicken was cooked, right? So, any viruses that may have been present were dead. And the chance of any viruses being present in the first place was pretty small. For those of you with more realistic questions, after doing a bit of research, here are some answers. Let’s start with…

Can I Catch Bird Flu from My Chickens?

Is it possible to catch avian flu after coming in contact with your infected flock? Short answer: Yes. Yes, it is. But, while the strain of bird flu that is currently circulating is very effective at killing chickens, it’s reaaaallly, reaaaallly unlikely to make you sick.

This year’s strain (an HPAI strain of A(H5N1) has sickened and killed millions of chickens and other birds, but there are only two known cases of people being infected.

In April, a Colorado poultry worker became infected with bird flu after handling sick birds during the process of euthanizing them. The worker reported fatigue for a few days as the only symptom, and was isolated and treated with oseltamivir, an antiviral drug. The worker has completely recovered.

In December, 2021, the owner of a bird flu-infected flock in the United Kingdom also became infected. The flock owner remained completely symptom-free.

Will you catch bird flu from your flock this year? Chances are pretty slim. But what about when the next outbreak of bird flu starts infecting flocks? While the current outbreak is waning, we can be sure that the next one is right around the corner. The only thing we don’t know is how far away that corner really is.

Study the Past – Know the Future

Confucius wisely suggested that you should “study the past if you would define the future.” So, while the H5N1 bird flu that’s currently making the rounds doesn’t seem to be very threatening to humans, we should take a Confucian approach and look at strains that have circulated in the past.

Compared to the strain of H5N1 causing this year’s avian flu outbreak, some of the H5N1 strains seen in the past have been much more likely to cause disease in humans. Important to understand: H5N1 flu consists of many, many strains, as does each subtype; H3N8, H5N1, H5N6, or whatever. Of the bazillions of flu strains that have been identified and named, a few are currently circulating in birds, humans, or some other animal, but most strains are no longer seen and are considered extinct.

According to Dr. Tim Uyeki, the Chief Medical Officer of CDC’s Influenza Division, this year’s H5N1 stain appears to be less adapted to infect humans than the H5N1 strains that were circulating before 2020. Dr. Uyeki notes that compared to the two human cases reported this year, 19 different countries reported human cases of H5N1 avian influenza to the World Health Organization between 2003 and 2021. Within those 19 countries, there was a total of 864 human cases in that period, resulting in the deaths of 456—over half!

When you look at the larger picture of avian flu subtypes other than H5N1, the number balloons. Among all subtypes, there have been over 3,100 reports of people infected with avian flu.

The Next Covid?

As I noted above, H5N1 bird flu has killed 456 people. That’s not an insignificant number, especially if you are a friend or loved one of one of those who died. But 456 deaths are a drop in the bucket compared to the deaths caused by Covid. The Covid death toll is approaching six and a half million. The difference between H5N1 and Covid is a matter of infectiousness. The unfortunate people who have succumbed to H5N1 caught the disease from poultry. In most cases people sick with H5N1 avian flu didn’t infect other people because the viruses have been poorly adapted to bind to human cells, thus unable to spread from human to human.

SARS-CoV-2, the Covid virus, is descended from a virus that lived in animals. Then, in 2019, that ancestral virus learned the trick of spreading among humans and became Covid. And because it has just learned this trick, no human had ever been infected with Covid before, and there was no level of immunity in any human, anywhere on earth. It could freely spread. By learning that trick, SARS-CoV-2 became a pandemic virus. It has killed millions, and it isn’t done.

Scientists who watch influenza are concerned about the possibility that a strain of avian flu could become the next Covid. Some strains have seemed adept at infecting humans. To be the next pandemic virus, one of those strains just needs to learn how to spread from human to human. SARS-CoV-2 learned that lesson. And past avian influenza viruses have learned that lesson as well, have become pandemic, and have sickened and killed millions of people.

How a Virus Learns to Cause a Pandemic: Mutation

In the previous article in this series, I talked about a “lock and key” analogy. Viruses can’t invade cells if they don’t have a specific “key” to fit the cell’s “lock.” A target cell’s “lock” is called the receptor molecule and the viral key is called a fusion protein. If the lock doesn’t fit the key, the viruses just bounce off the cells and can’t get in. Viruses have to “learn” how to make a new key if they want to invade the cells of a new species. Learning is simply a matter of getting the right information. Viruses “learn—e.g., get the right information” by genetic mutation.

CDC’s Dr. Uyeki puts it this way: “For avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses currently circulating among birds to develop the ability to infect and spread among people, several things would need to happen, including mutations that would allow the virus to bind efficiently to epithelial cells of the human upper respiratory tract, and to facilitate sustained transmission from person-to-person.”

Flu viruses and their RNA virus cousins mutate a lot! One type of mutation is called a “point mutation.” A point mutation happens when one bit of information (one nucleotide) gets switched around. All living things can make an occasional mistake and switch single nucleotides when their cells divide.

Viruses can’t reproduce on their own. They hijack the machinery of the cells of other organisms to make new baby viruses. When RNA virus hijacks a cell, the rate of point mutations can go up a millionfold. Because flu viruses are undergoing constant point mutations as they reproduce, they are gradually and constantly changing—mutating! Thus, flu viruses are gradually and constantly evolving into new strains of flu.

This gradual and constant change in flu viruses is called “antigenic drift.” The new and slightly different flu strains created by antigenic drift is what causes seasonal flu, and is why we all have to roll up our sleeves for a new flu shot every year.

There’s another type of viral mutation that is a lot more scary than antigenic drift. Imagine you are one of the unfortunate folks who caught bird flu from your chickens. You are truly unfortunate. Because of the “lock and key” thing, most avian flu viruses have a hard time getting into human cells. But maybe you’ve helped things along—you’ve been so sad about your sick and dying hens that you’ve hugged and kissed them—perhaps a natural reaction, but also a way of guaranteeing that you’ve gotten a big old dose of virus. So, sadly, you’ve caught bird flu from your chickens. Now imagine that you are really unlucky and already have flu—the seasonal human variety that’s making the rounds.

Now you’ve got two different flu viruses reproducing inside your cells. During the reproduction process, these two viruses can swap out an entire influenza gene segment. This process actually happens and it’s called “reassortment” and this scenario is referred to as “the mixing bowl phenomenon.” It can occur in people, but it is even more prevalent in pigs, because the “locks” on their cells can be opened by keys that normally fit the cells of birds OR humans. The mutations caused by reassortment is called “antigenic shift” and can result in sudden, profound changes to a virus. One possible profound change: A flu virus that can only spread in birds acquires the “key” to be able to spread from human to human. It essentially becomes a new virus that humans have never encountered before and have no immunity to. We know what happens next, right? A human pandemic.

Can I Catch Bird Flu from My Chickens?

Take a deep breath. Are you going to catch flu from your chickens? Are you going to be the first victim of the next pandemic?

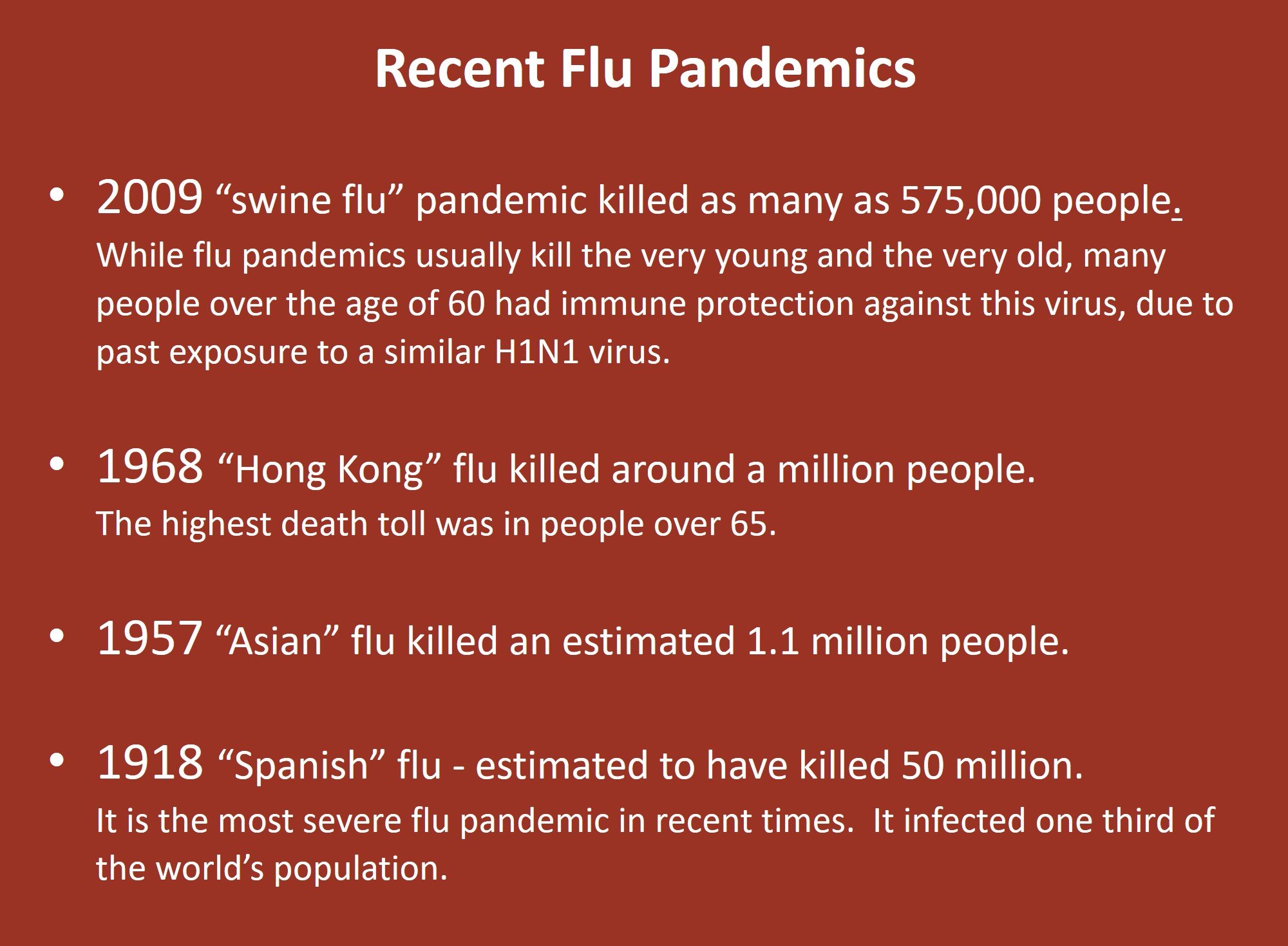

Flu pandemics don’t happen very often. Flu viruses keep trying, but all the conditions have to be just right. Four flu pandemics have occurred in the last 100 years—in 1918, 1957, 1968 and 2009. There have been nine influenza pandemics in the past 300 years, so if you do the math, you can expect one every 30 years or so. But doing the math is a pointless exercise because all of the pandemic-necessary factors clicking into place at the right time is totally a matter of random chance.

The 2009 flu pandemic was the first one this century. As pandemics go, it wasn’t so bad. Then out of left field, we were hit with the devastating Covid pandemic. Will there be another pandemic next year? Will we have five more this century or are we done for the next hundred years? It’s roulette. Random chance. Nobody knows.

Will you catch flu from your chickens? While outbreaks of avian flu will undoubtedly continue to circulate in the future, you can only catch flu from your chickens if they have flu. Practicing good biosecurity will reduce the chances of them becoming infected. Then, the strain they become infected with would have to be one that has mutated to a form that is at least slightly compatible with human upper respiratory epithelial cells. Then, if you were to handle and interact with your obviously sick chickens, you may become infected.

The avian flu circulating this year, of course, has shown no affinity for people. Will there be circulating avian flu strains in the future that are more likely to infect people? Probably. Will somebody catch flu from their chickens? Undoubtedly. Will somebody win Powerball? Without question. Will that “somebody” who catches flu from their chickens be you? Will that Powerball winner be you? Probably not.