Marek’s Disease: 8 Questions - 8 Answers (Plus, The Scoop on Home Vaccination)

Readers: Back in August of 2018 I published a post entitled “Marek’s Disease—Six Things You Should Know.” It was a long article, somewhat technical, and the subject was not a happy one; a devastating, worldwide disease that kills and maims chickens. It has proved to be one of my most popular posts, with large numbers of people clicking onto my site to read it every day. People obviously want to know more about this disease. I take a look at the article myself from time to time, and usually come away thinking of things I would like to add or say a bit differently. So I recently rolled up my sleeves and got to work making those changes. It turned into a complete rewrite. And here it is.

What’s the real deal with Marek’s Disease? As a flock-keeper, I’ve accumulated bits and pieces of information about this terrible viral disease and am aware that it can sicken and destroy entire flocks. Whenever I’ve brought babies home from the hatchery, I’ve always opted to have them vaccinated. But beyond that I haven’t spent a lot of time worrying about it. I first began to seriously consider the disease and its consequences as I prepared to bring home six baby Silkie chicks from a local breeder, who, like most small local breeders, does not vaccinate.

My flock, like most flocks, is made up of birds that have come from a variety of sources. Some have come from commercial hatcheries and are vaccinated. Others are from breeders that don’t vaccinate, and then there are some that I picked up at local farm stores and I’m clueless about their vaccination status. Like all flock keepers, I’ve lost some hens over the years. The cause of some of those deaths was unclear – sometimes the set of symptoms just don’t match any of the usual chicken diseases. And while I mourn the loss of each of my hens, I have not considered necropsy or diagnosis important if everybody else seemed healthy – a philosophy that I’m currently rethinking. Could some of those deaths have been due to Marek’s? Who knows? Marek’s symptoms can be nonspecific, variable, and consistent with a variety of other diseases.

So, with the imminent arrival of my new chicks, the questions running through my mind were “Should I be testing my flock?” Followed by “Is testing even possible?” And “Should I vaccinate these new little guys?” Followed by “How do I vaccinate them?” Followed by “Is home vaccination even possible?” Other questions filtered through my brain one after the other: “What’s the real Marek’s risk to my flock? What strategies can I exercise to prevent it? AND, “Is it really that serious?” I decided it was time to do some research. The paragraphs that follow contain some of the information I was able to glean from veterinary articles, scientific journals, chicken health experts and various online resources. I’m sharing it here with the hope that it may be useful to you. Bear in mind that I’m not a Marek’s expert or a vet. I’m merely a chicken owner sharing information. Also, keep in mind that this is just a short thumbnail of a very complex disease.

1 - Do I have Marek’s Disease in my Flock?

Marek’s Disease is as confusing as it is frightening and devastating. It was first characterized in the early 20th century by the Hungarian vet, Dr. József Marek who was probably unaware that his name would be permanently linked to a disease that would strike fear into the hearts of poultry-keepers everywhere. Because Marek’s manifests a variety of different symptoms and many of those same symptoms occur in other diseases, many flock keepers aren’t aware that Marek’s is lurking in their flock. And many flock keepers don’t realize that no matter how stringent they are in their husbandry practices and no matter how meticulously clean their coop; their flock still has a high potential for Marek’s. If you’re concerned about the potential for Marek’s in your coop, I suggest you take this easy two-step Marek’s detection test right now. 1—Go to your coop. 2—Open the door and look. Do you see chickens? Then your potential for Marek’s is high. An exaggeration? Perhaps not. The Merck Veterinary Manual, a reference used by vets everywhere and not known for hyperbole declares that “Marek disease is one of the most ubiquitous avian infections; it is identified in chicken flocks worldwide. Every flock, except for those maintained under strict pathogen-free conditions, is presumed to be infected.” Does this mean that Marek’s is lurking in your flock? Not necessarily. But if we all presumed our flocks were infected and acted accordingly, we would all be one step closer toward controlling this devastating disease.

2 - How Bad Is It, Anyway?

The severity of a Marek’s Disease outbreak in your flock can vary depending on a number of factors. Susceptibility can vary from breed to breed and even line to line. I’ve seen several reports that Silkies and Seabrights are especially vulnerable. Young chickens are more vulnerable – chicks can become infected the moment they hatch. The disease is most commonly seen in youngsters 12 – 24 weeks old, and some forms of Marek’s can cause a mortality rate of 70% in unvaccinated birds of that age.

Properly vaccinated chickens will probably never get sick, but unfortunately, Marek’s vaccine is a “leaky vaccine” – vaccinated chickens may never develop symptoms but if they come in contact with the virus at any point post-vaccination, they can still become infected, carry it inside their bodies, and pass it along to other chickens. I’m going to repeat that important point for emphasis: Vaccination for Marek’s may prevent symptoms, but chickens, regardless of whether or not they’ve been vaccinated, when exposed to Marek’s disease can still acquire and carry the virus and infect other birds. So, if you’re certain that you’ve lost chickens to Marek’s, it is very likely that your entire flock, even those previously vaccinated hens that appear healthy, are carrying and shedding the virus.

3 – How Do Chickens Get Marek’s Disease?

Imagine a virus that can invade your body with the air you breathe, like the COVID-19 virus. Then, imagine that virus can take over your body in the same way HIV takes over in a patient with AIDS. And further imagine that the virus can hide out inside your body’s cells, making it hard to treat and also hard to detect. That virus would be a nightmare. In chickens, that nightmare is Marek’s. Marek’s Disease is caused by a herpes virus. You’ve probably heard of herpes viruses in connection with genital herpes in humans – a viral disease that is hard to treat and sometimes hard to detect because it can hide out inside nerve cells. That’s one of many diseases the various herpes viruses can cause. Herpes viruses are also responsible for the human diseases chicken pox, shingles, and mono. Certain herpes viruses can cause a variety of cancers in humans, and that’s exactly what the Marek’s herpes virus does in chickens.

It happens like this: The Marek’s Disease virus lives in the feather follicles of infected chickens and escapes into the environment as the chicken sheds dander. The virus can happily survive inside these bits of dander for months and in some cases over a year. Then, an unsuspecting chicken inhales that speck of dander. The virus, still riding on the dander, goes deep into the chicken’s lungs, comes to rest on the epithelial cells of the lung and begins the invasion. The virus enters the epithelial cells and takes over. The chicken’s immune system responds to this infection and white blood cells rush to the lungs to fight the infection. One type of white blood cell that responds to the infection is called a CD4 T-cell – and is also referred to as a “helper cell” because it is this cell that alerts the body that there’s an infectious agent lurking. Marek’s virus, unfortunately, specializes in hijacking helper cells. The virus hops off the lung cells and onto the helper cells and takes over. It’s a very neat trick – not only does this suppress the chicken’s immune response, but the virus can use the helper cells like taxis and zip around the chicken’s body to set up other sites of infection. This neat trick is not unique to the Marek’s virus; HIV invades humans exactly the same way – by hijacking helper cells.

By the end of a week the Marek’s virus is living in and reproducing in white blood cells throughout the chicken’s body. Also, before the first week is finished, the virus has already found its way to the chicken’s feather follicles and the chicken is actively shedding viruses in her feather debris and dander. Three to four weeks after infection, helper cells have taxied viruses to the various major nerves and organs and the viruses have begun to transform their host cells into cancerous tumors. It is only then that the chicken starts to show symptoms. Death usually follows in a couple of weeks although some chickens do survive, but may be permanently affected by their bout with the disease, and without a doubt will continue to shed virus.

If the chicken is healthy, not stressed, and has good genetics, or if she has been vaccinated, she may not show any symptoms. But more than likely this seemingly healthy, vaccinated chicken will become infected. The virus works its way into her cells and while she doesn’t become symptomatically sick, she becomes a virus factory and can churn out Marek’s virus that will infect other chickens.

4 – What Does Marek’s Disease Look Like?

Marek’s symptoms can be very different from chicken to chicken. Because tumors can form in a number of different tissues, organs, or nerves, Marek’s can manifest with a variety of symptoms, with one or more of these manifestations occurring in any individual chicken. The wide range of symptoms makes it difficult for the uninitiated flock keeper to realize that his hens are all suffering from the same virus. And even the savvy chicken owner can’t always be entirely sure that his chickens are dying from Marek’s or something else. Disease presentations can include:

Classic Marek’s paralysis pose (photo: University of MN Extension)

Immune system suppression. With a weakened immune system, chickens can become more susceptible to other diseases such as coccidiosis that may have been in the background all along. It would be very easy, in this instance, to assume that the chicken had to succumbed to a particularly nasty case of coccidiosis and have no suspicion about Marek’s.

“Classic” Visceral Marek’s Disease: This form of the disease results from viral tumor formation in peripheral nerves and is usually seen in young chickens between six and twenty-four weeks old. It presents as partial paralysis—often the bird will sit with one leg to the front and one leg to the back, or one wing may droop and drag. “Torticollis” or twisted neck occurs when the nerves controlling the neck are affected. If the vagal nerve is affected, the crop may stay permanently dilated, or the bird will have problems breathing. Tumors can also form in the lungs, liver, kidneys, or ovary. This can be the most devastating form of the disease, and can reach a mortality rate of 70% in young, unvaccinated chickens.

Cutaneous Marek’s: Skin involvement can range from skin nodules to non-healing lesions or bleeding feather follicles.

Encephalitis: The viral tumors form in young chickens’ brains, resulting in rapid paralysis and death.

Ocular Marek’s: When tumors form in the eye or on the optic nerve, the pupil in one or both eyes can become tiny and not enlarge in response to light. Or the iris may become gray and misshapen. The chicken becomes functionally blind.

Sudden Death: Sometimes the only apparent symptoms are loss of appetite and weight or diarrhea. And sometimes there are no obvious symptoms at all, and your apparently healthy chicken just suddenly and spontaneously dies.

5 - How Can I Be Sure My Flock Has Marek’s?

There are tests for Marek’s and while you may never opt to have testing done, it’s useful and important for you to understand what those tests are so you can make an informed decision if you think you have Marek’s Disease in your flock. It’s going to get a little sciencey in this section, so bear with me as I try to keep it simple while keeping it accurate.

The Classic Method – Necropsy:

“Necropsy” is simply the word for an autopsy performed on an animal. (A bit of trivia that you will never ever be able to use anywhere—the Greek root word “necro” means “dead.” The Greek root word “psy” means “study of.” Thus, necropsy is studying dead things. The Greek root word “auto” in “autopsy” means self—thus, with autopsy, we humans are doing a necropsy on one of our own. Try throwing this factoid out there as light banter at your next cocktail party and watch everybody sort of slide away from you as the party goes necrotic.) Obviously, performing a necropsy requires that there be a dead chicken. If your flock has become acutely infected with Marek’s, you unfortunately probably have more than one. The features the examiner looks for to diagnose Marek’s includes an enlargement and a change in appearance of certain peripheral nerves, enlarged feather follicles, and most importantly, nodular lymphoid tumors in specific organs, including the liver, spleen, heart, lung, and kidney.

If the examiner sees the features I described, they will issue a diagnosis of “presumptive” Marek’s disease. Because these necropsy finding can also be seen in other diseases, this presumptive diagnosis should be confirmed by testing for the actual Marek’s Disease virus, which is usually done with an assay called “PCR.”

The Molecular Method—PCR:

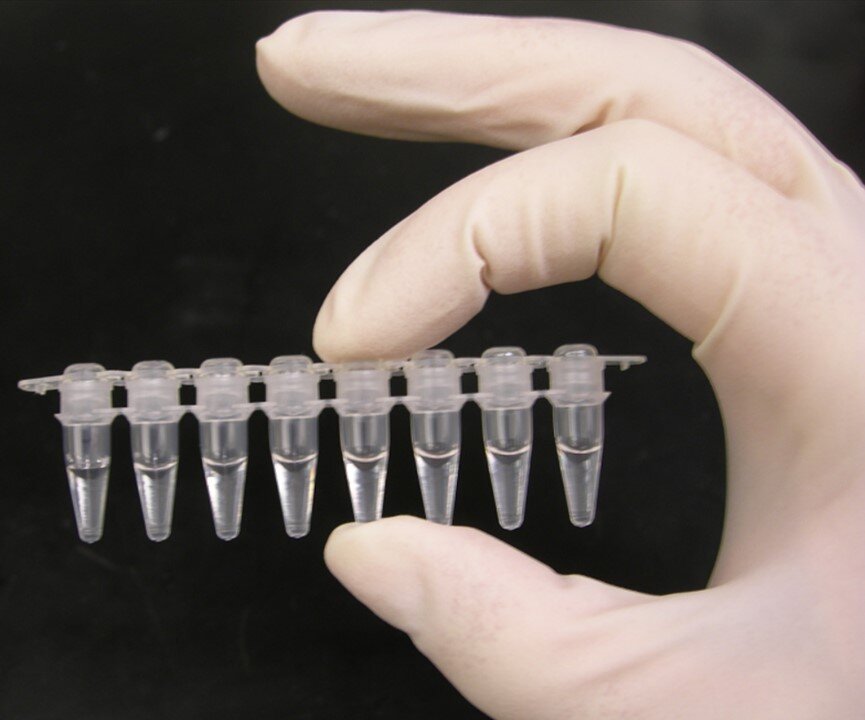

Photo: Madeleine Price Ball

PCR testing can be performed on blood from a living chicken or on tissue—usually from a necropsy. The Marek’s Disease virus PCR test looks for a “genome sequence” that is specific for the Marek’s Disease virus. Finding that sequence tells you that you’ve found the virus. And that’s all you really need to know. If you would like a little more information on PCR, read on.

Otherwise, skip right down to the next section!

PCR is the abbreviation for Polymerase Chain Reaction, a technique used by molecular microbiologists to make a bazillion copies of specific chunks (e.g. a genome sequence) of the nucleic acids in the cells of living things. Nucleic acids essentially come in two flavors—RNA and DNA. You have probably heard of them; they’re the chemical blueprint in the middle of every cell of every living thing that determines the characteristics of that living thing. Thus, the DNA in chicken cells direct the cells to form into a fully functioning chicken. And the same applies to the DNA in whales, geraniums, Marek’s Disease virus, and every other living thing. One of the things nucleic acids do is reproduce by making copies of themselves. PCR hijacks this function and gets the nucleic acids to churn out bazillions of copies of themselves (or, more accurately, specific targeted parts of themselves) in very rapid fashion.

So, you make a bazillion copies of a chunk of the DNA of the virus. Big deal! How is this practically useful? Here’s how: Imagine you’ve got a sample that contains one lonely Marek’s Disease virus. If you could test for the DNA of that virus, you would know Marek’s was there since DNA is the specific blueprint for the organism it comes from. Find Marek’s DNA and you’ve found Marek’s virus. But there is no way to detect the DNA of one virus—it would be like finding a needle in a haystack. However, if you run PCR, you amplify a chunk of the DNA of that virus billions of times – and pretty soon you’ve got a whole heap of chunks. Enough that you can detect it using any number of methods. If you don’t detect Marek’s DNA after running PCR it means there was nothing to amplify—no virus in the original sample—a negative result. Whew. Those last couple of paragraphs were a crazy science party! Going back and reading them again is totally OK—it’ll be just as much fun the second time around!

What does a negative PCR test mean?

It means that that no Marek’s Disease virus was present in the sample that was tested. It does not mean that there was no virus somewhere else in the bird the sample came from. Unfortunately, the Marek’s Disease virus has a trick that it shares with many of its herpes cousins—latency. It can hide out in cells for months or years—it isn’t actively making tumors, but it is still infecting the chicken and that chicken can still shed virus with its dander and infect other chickens. And because the amount of virus is so low during latency, the sample that is tested may contain no virus at all, and would yield a negative result. Since the amount of virus in latent infections is higher in certain organs like the liver and the spleen, more accurate results are obtained by testing those organs rather than blood. But that means, of course, that you have to test necropsy samples and not samples from living chickens.

What does a positive PCR test mean?

Merck’s Manual cautions that it is “critical to diagnose the tumors and not the infection.” In other words, if you can presumptively diagnose Marek’s with a necropsy, a positive finding for the virus by PCR nails the specific diagnosis of Marek’s Disease. But a positive PCR without necropsy results is meaningless because, in Merck’s estimation, the virus is practically everywhere and infection does not mean disease.

The final scoop on PCR testing:

PCR can be an important piece of the diagnostic puzzle, but on their own, PCR results can be meaningless.

Where to Go for Testing:

If you have an avian vet in your area, they probably will perform necropsies. If you don’t have an avian vet, or your vet does not do necropsies, most state veterinary labs will necropsy chickens. While only some state vet labs do PCR testing, most will refer samples on to other labs for PCR testing. You can find your state lab here. A few state vet labs will perform necropsies free-of-charge, but most have fees that can be as much as several hundred dollars. A PCR test can also cost several hundred dollars.

6 – How Can I Stop Marek’s Disease?

If Marek’s strikes your flock there’s very little you can do except suffer as your sick chickens suffer, and end their suffering when it becomes severe. There is no cure.

Your best strategy is to shield your flock from the grips of Marek’s Disease in the first place. While there are three prevention strategies, they are all, unfortunately, sometimes hard to follow.

Genetics:

There have been reports that certain breeds, like Silkies, are more susceptible to Marek’s and other breeds, like Fayoumis, are more resistant. These reports are, as far as I know, anecdotal. Lacking any firm statistics on Marek’s resistance by breed, depending on certain breeds to be more resistant to the disease is probably not the best strategy.

Biosecurity:

Commercial chicken operations with hundreds of thousands of chickens at one location rarely let outsiders onto the premises and those who absolutely need to enter the facility are often garbed in Tyvek suits and boots and nitrile gloves. They take biosecurity very seriously. Backyard chicken folks take biosecurity not so seriously. Neighbors meander in and out—some of those neighbors have chickens of their own. When the chicken owners go on vacation, the chicken sitter comes, and that chicken sitter may be traveling in and out of several other coops on any given day. There are coop tours where large groups of people wander from coop to coop. Chicken folks go to the chicken barn at the fair and then come home and tend their flocks. They go to swap meets and bring home chickens from strange flocks. All of these activities can transmit disease. Bear in mind that to transmit Marek’s you don’t need to go tramping through the chicken poop in a strange chicken yard—all you need is to carry a little bit of chicken dander home on your sleeve. If you’re serious about using biosecurity to protect your flock from Marek’s, you need to enact strict rules and you need to enforce those rules:

Don’t visit other coops.

Don’t allow any unnecessary people near your chickens or in your coop.

If you must allow a caregiver or someone else in your coop, and they’ve been in contact with another coop or flock, make sure that they’ve showered and changed clothes before visiting your coop.

Do NOT attend coop tours, don't enter poultry barns at the fair, don't go to swap meets or anywhere else where there are live chickens.

Don’t enter your chickens in exhibitions or shows where they can come into contact with large numbers of birds from other flocks.

Don’t introduce new adult chickens to your flock that come from other backyard flocks. Quarantining the new bird for any length of time will not protect your flock from the asymptomatic carrier.

You are probably shaking your head and gritting your teeth by this point. In the real world, you’re just going to do a lot of the things listed in the bullets above. So, do them! Just realize that there’s a risk. HOWEVER (please note bolded, italicized, all caps!) If you suspect you have Marek’s in your flock, showing, trading, or selling chickens moves from risky behavior to unethical behavior. In this circumstance, at the very least, you should draw some blood from some of your chickens and send it off for Marek’s testing. As I already discussed in section 5, a negative blood test is meaningless, but if you get a positive test, you have definitive proof that you need to close your flock and stop all trading, showing, and selling.

Disinfect! Disinfect any tool or object you bring into your coop that may have been in contact with another flock. And periodically do a thorough cleaning of your coop, then scrub it with detergent, and then get it sloppy wet with a good disinfectant. (Here’s a coop cleaning checklist from the USDA) Some important news about disinfectants: Vinegar is not going to do the job. Laundry bleach is a bit better, but don’t use it! Sodium hypochlorite, the active ingredient in bleach degrades over time, and degrades even more quickly once you’ve diluted it with water. And if you’re using it on dirty surfaces, any organic material present will neutralize it. Go to your local farm store and see what they’ve got for real, proven disinfectants. Read the labels; you want something with virucidal properties. Activated Oxine and Virkon S are two examples of virucidal disinfectants. Be sure to thoroughly follow the safety precautions that are printed on the labels; disinfectants can be harmful to humans and chickens. Not surprising really, since they are chemicals designed to kill stuff. And finally, bear in mind that if you already have Marek’s in your flock disinfecting the coop is not going to get rid of the viruses living in your chickens. But it will get rid of any other viruses, bacteria and parasites that could affect the health of your flock, and it will reduce the amount of Marek’s virus in coop environment that could blow out or be tracked or carried out and spread elsewhere.

Buy babies from hatcheries that vaccinate—preferable those that use a bivalent or trivalent vaccine (more on vaccination coming up!)

If you buy babies from a breeder or hatchery that doesn’t vaccinate, vaccinate the babies yourself—within couple days of hatching, and preferably when they are less than a day old. After vaccination, maintain the babies in strict isolation for 3-5 weeks.

I’ll be the first to say that these rules are stringent. Do you know anybody who follows all these rules to protect their backyard flock? I know I don’t. But perhaps we all should.

Vaccination:

You may be a little discouraged after having read what I had to say about genetics and biosecurity and perhaps you’re holding great hope for what I have to say about vaccination. Well, here’s the good news: Vaccine manufacturers and hatcheries will tell you that vaccines have an effectiveness of greater than 90%. While that statistic is undoubtedly true since it’s based on hard evidence, you need to bear in mind that for the vaccine to work, it has to be administered correctly and at the right time. Also, since the virus is capable of mutating to more resistant forms, the current vaccines will without a doubt become less effective as time goes on. There are currently three different varieties or “serotypes” of vaccine—each is made from a different strain of the virus:

Serotype 3 vaccine is made from a strain of Marek’s virus that occurs in turkeys that does not cause disease in chickens. It’s also referred to as Herpes Virus turkey (HVT). It was developed in the 1970’s in Michigan and is the oldest of the vaccines, thus it’s the least effective serotype due to mutated resistance.

Serotype 2 vaccine is made from a strain of virus that naturally occurs in chickens but doesn’t cause tumor formation or disease.

Serotype 1 vaccines (there are several of them) are made from the disease-causing virus. These vaccines are “attenuated”—they’ve been manipulated in a laboratory to weaken their ability to cause disease but they still cause immunity in the chicken that receives the vaccine.

Bivalent and Trivalent Vaccines: Serotype 1 vaccine when given in a “bivalent” vaccine combined with Serotype 3 vaccine, is more effective than either serotypes 1 or 3 given separately. Most hatcheries, as standard practice, give the bivalent vaccine or a trivalent vaccine that contains all three serotypes.

“Booster” Vaccination: Several studies in the last few years have demonstrated that a second vaccination improves protection against Marek’s disease. One publication showed that the most beneficial revaccination strategy was to administer the first dose when the chick was still in the egg and the second dose right after hatching. I am not aware of any hatcheries actually pursuing this strategy, but when you buy chicks from a hatchery, it wouldn’t hurt to ask what vaccine(s) they use and what their vaccination strategy is.

And finally, I’m going to repeat a fact that I’ve already mentioned a couple times, because it’s important: An effective Marek’s vaccine will prevent tumors from forming in a vaccinated chicken. It will NOT (unlike most vaccines against other diseases) prevent an exposed chicken from becoming infected with Marek’s virus. SO, if your vaccinated chicken becomes exposed to Marek’s your chicken will probably not get sick. But it is likely that your chicken will become infected with Marek’s and become a carrier. And that’s the big problem with Marek’s vaccine. Since vaccinated chickens don’t get sick and die, but can carry the virus, there is a large pool of carrier chickens where the virus can live and mutate to new forms.

7 – What Are the Logistical Difficulties with Home Vaccination?

OK, vaccines are a good thing—they save chickens’ lives. If you buy vaccinated chicks your flock is probably safe from Marek’s. But if you buy chicks from some other source and plan on vaccinating at home the situation becomes a little dicier. Here is a short list of some of the problems you’ll have to consider:

The only vaccine available to backyard chicken keepers is the serotype 3 vaccine. It’s an effective vaccine, but as I mentioned before, because it’s the oldest vaccine, it’s becoming less effective due to mutated viral resistance.

It needs to be stored really cold—in liquid nitrogen—until it’s thawed for use. If you don’t have a local supplier (you probably don’t) you need to buy it from an on-line supplier and it needs to be shipped cold, overnight express. If it gets warm in shipment, it will not work.

It is only available in 1000 dose vials. How many chickens are in your backyard flock?

Once you’ve opened the vaccine and mixed it, it’s good for an hour. So, there’s no possibility of using some and throwing the left-overs in the freezer for next year’s baby chicks.

The manufacturer’s instructions are to use it on chicks less than a day old. Some hatcheries actually vaccinate while the chick is still in the shell. If you wait until the chick is older to vaccinate, the vaccine won’t harm the chick, but it may be useless. Every second that ticks by after a chick hatches increases the window of opportunity for the chick to be exposed to Marek’s virus. If exposure occurs before vaccination, the vaccine will not work.

The actual vaccination involves administering 0.2 cc of vaccine into the neck of the chick. How are you at poking needles into tiny, fluffy chicks?

After giving your chicks the vaccine, you have to be meticulously careful that they aren’t exposed to other chickens or any source (chicken dander on your sleeve, for instance) of virus for at least two weeks, and preferably up to six weeks.

8 – How Do I Vaccinate My Chicks?

You can do this! I did! Here’s how: I checked around with various other flock keepers and local chicken forums to see if I could find a local source for Marek’s vaccine. I could not. So, then I turned to the trusty internet. Valley Vet Supply an on-line animal pharmacy located in Maryville, Kansas, has serotype 3 vaccine made by Zoetis. For $29.95 I could get a 1000 dose vial—the only size available. The overnight shipping charge was $22.50. Thus, the total order was $52.45. After I placed the order, I found a local small animal vet who is willing to order vaccine for me with her weekly vaccine order in the future. She doesn’t use this vaccine or treat chickens, but ordering the vaccine as part of her shipment will save me the cost of shipping. I also ordered 10-pack of syringes from an online retailer for $8.99.

I had the vaccine on hand when brought my babies home. The vaccination procedure was simple. I reconstituted the vaccine with the provided diluent, and preloaded six syringes with 0.2 cc of vaccine. Then, one-by-one I swabbed the back of each chick’s neck with alcohol, pinched the skin on the back of their necks and injected the vaccine into the fold of skin. Afterwards, since the vaccine contains live virus, I boiled the remaining vaccine, the vial, and the syringes. I disposed of the syringes at my local sharps disposal site.

If you do the math, vaccinating my six baby Silkies cost me $10.24 per chick. Was it worth the expense? What would you be willing to pay to save the life of your pet chicken?

One final thing: This post, as I already said, is a thumbnail. A great source for more information about Marek’s Disease is a huge, comprehensive, and well-maintained Marek’s FAQ on the BackYard Chickens forum. That compendium of information is aimed at backyard flock keepers and was compiled by backyard flock keeper Jennifer Miller aka "Nambroth" after she lost her “sweet and wonderful Cochin rooster,” Trousers, to the disease. While she claims not to be a professional or expert, she is perhaps the most well-informed amateur on the planet after years of compiling and maintaining this collection of information.

Several studies have identified Marek’s Disease as the main killer of backyard chickens. To learn about the other main causes of death in backyard flocks take a look at “What’s Killing Our Backyard Chickens.”